Saint Hildegard of Bingen

Saint Hildegard of Bingen

Mystic, Germany. 35th Doctor of the Church

1098 - 1179

Feast September 17

"This "prophetess" who also speaks with great timeliness to us today, with her courageous ability to discern the signs of the times, her love for creation, her medicine, her poetry, her music, which today has been reconstructed, her love for Christ and for his Church which was suffering in that period too, wounded also in that time by the sins of both priests and lay people... thus St Hildegard speaks to us. -Benedict XVI, Sept, 2010

The Church puts before us the saints as witnesses of God's work and our models. It is notable that Pope Benedict XVI has chosen a woman mystic, well known for her visions and courage to reform the Church, to be formally canonized (May 10, 2012) and declared Doctor of the Church (October 7, 2012). Last year he canonized another mystic and visionary: Blessed Elena Aiello.

Throughout the centuries, four attempts to canonize Hildegard failed, even though her name is in the Roman Martyrology since the end of the sixteenth century. But Christ is now presenting her to us as a Doctor of the Church.

Quotes

The soul is kissed by God in its innermost regions. With interior yearning, grace and blessing are bestowed. It is a yearning to take on God's gentle yoke, It is a yearning to give one's self to God's Way. - attributed, Soul Weavings

May the Holy Spirit enkindle you with the fire of His Love so that you may persevere, unfailingly, in the love of His service. Thus you may merit to become, at last, a living stone in the celestial Jerusalem. - letter to the Monk Guibert

Sept 1, 2010

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In 1988, on the occasion of the Marian Year, Venerable John Paul II wrote an Apostolic Letter entitled Mulieris Dignitatem on the precious role that women have played and play in the life of the Church. "The Church", one reads in it, "gives thanks for all the manifestations of the feminine "genius' which have appeared in the course of history, in the midst of all peoples and nations; she gives thanks for all the charisms that the Holy Spirit distributes to women in the history of the People of God, for all the victories which she owes to their faith, hope and charity: she gives thanks for all the fruits of feminine holiness" (n. 31).

Various female figures stand out for the holiness of their lives and the wealth of their teaching even in those centuries of history that we usually call the Middle Ages. Today I would like to begin to present one of them to you: St Hildegard of Bingen, who lived in Germany in the 12th century. She was born in 1098, probably at Bermersheim, Rhineland, not far from Alzey, and died in 1179 at the age of 81, in spite of having always been in poor health. Hildegard belonged to a large noble family and her parents dedicated her to God from birth for his service. At the age of eight she was offered for the religious state (in accordance with the Rule of St Benedict, chapter 59), and, to ensure that she received an appropriate human and Christian formation, she was entrusted to the care of the consecrated widow Uda of Gölklheim and then to Jutta of Spanheim who had taken the veil at the Benedictine Monastery of St Disibodenberg. A small cloistered women's monastery was developing there that followed the Rule of St Benedict. Hildegard was clothed by Bishop Otto of Bamberg and in 1136, upon the death of Mother Jutta who had become the community magistra (Prioress), the sisters chose Hildegard to succeed her. She fulfilled this office making the most of her gifts as a woman of culture and of lofty spirituality, capable of dealing competently with the organizational aspects of cloistered life. A few years later, partly because of the increasing number of young women who were knocking at the monastery door, Hildegard broke away from the dominating male monastery of St Disibodenburg with her community, taking it to Bingen, calling it after St Rupert and here she spent the rest of her days. Her manner of exercising the ministry of authority is an example for every religious community: she inspired holy emulation in the practice of good to such an extent that, as time was to tell, both the mother and her daughters competed in mutual esteem and in serving each other.

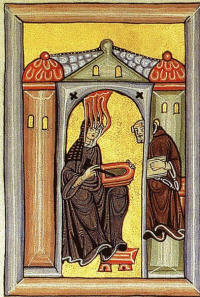

During the years when she was superior of the Monastery of St Disibodenberg, Hildegard began to dictate the mystical visions that she had been receiving for some time to the monk Volmar, her spiritual director, and to Richardis di Strade, her secretary, a sister of whom she was very fond. As always happens in the life of true mystics, Hildegard too wanted to put herself under the authority of wise people to discern the origin of her visions, fearing that they were the product of illusions and did not come from God. She thus turned to a person who was most highly esteemed in the Church in those times: St Bernard of Clairvaux, of whom I have already spoken in several Catecheses. He calmed and encouraged Hildegard. However, in 1147 she received a further, very important approval. Pope Eugene III, who was presiding at a Synod in Trier, read a text dictated by Hildegard presented to him by Archbishop Henry of Mainz. The Pope authorized the mystic to write down her visions and to speak in public. From that moment Hildegard's spiritual prestige continued to grow so that her contemporaries called her the "Teutonic prophetess". This, dear friends, is the seal of an authentic experience of the Holy Spirit, the source of every charism: the person endowed with supernatural gifts never boasts of them, never flaunts them and, above all, shows complete obedience to the ecclesial authority. Every gift bestowed by the Holy Spirit, is in fact intended for the edification of the Church and the Church, through her Pastors, recognizes its authenticity.

I shall speak again next Wednesday about this great woman, this "prophetess" who also speaks with great timeliness to us today, with her courageous ability to discern the signs of the times, her love for creation, her medicine, her poetry, her music, which today has been reconstructed, her love for Christ and for his Church which was suffering in that period too, wounded also in that time by the sins of both priests and lay people, and far better loved as the Body of Christ. Thus St Hildegard speaks to us; we shall speak of her again next Wednesday. Thank you for your attention.

Continuing reflexion on St Hildegard

Excerpts from Benedict XVI's address on St. Hildegard Full text

"Theology As Well Can Receive a Particular Contribution From Women"

Sept 8, 2010

St. Hildegard of Bingen, an important woman of the Middle Ages, who is distinguished for her spiritual wisdom and holiness. Hildegard's mystical visions are like those of the prophets of the Old Testament: Expressing herself with the cultural and religious categories of her time, she interpreted sacred Scripture in the light of God, applying it to the various circumstances of life. Thus, all those who listened to her felt exhorted to practice a coherent and committed style of Christian living. In a letter to St. Bernard, the Rhenish mystic says: "The vision enthralled my whole being: I do not see merely with the eyes of the body, but mysteries appear to me in the spirit ... I know the profound meaning of what is expressed in the Psalter, in the Gospels and in other books, which were shown to me in the vision. This burns like a flame in my breast and in my soul, and teaches me how to understand the text profoundly" (Epistolarium pars prima I-XC: CCCM 91).

With the characteristic traits of feminine sensitivity, Hildegard, specifically in the central section of her work, develops the subject of the mystical marriage between God and humanity accomplished in the Incarnation. Carried out on the tree of the cross was the marriage of the Son of God with the Church, his Bride, filled with the grace of being capable of giving God new children, in the love of the Holy Spirit (cf. Visio tertia: PL 197, 453c.).

Already from these brief citations we see how theology as well can receive a particular contribution from women, because they are capable of speaking of God and of the mysteries of the faith with their specific intelligence and sensitivity. Hence, I encourage all those [women] who carry out this service to do so with a profound ecclesial spirit, nourishing their own reflection with prayer and looking to the great wealth, in part yet unexplored, of the Medieval mystical tradition, above all that represented by luminous models, such as, specifically, Hildegard of Bingen.

Finally, in other writings Hildegard manifests a variety of interests and the cultural vivacity of women's monasteries in the Middle Ages, contrary to the prejudices that still today are leveled upon that epoch. Hildegard was involved with medicine and the natural sciences, as well as with music, being gifted with artistic talent. She even composed hymns, antiphons and songs, collected under the title "Symphonia Harmoniae Caelestium Revelationum" (Symphony of the Harmony of the Celestial Revelations), which were joyfully performed in her monasteries, spreading an atmosphere of serenity, and which have come down to us. For her, the whole of creation is a symphony of the Holy Spirit, who in himself is joy and jubilation.

The popularity with which Hildegard was surrounded moved many persons to seek her counsel. Because of this, we have available to us many of her letters. Masculine and feminine monastic communities, bishops and abbots turned to her. Many of her answers are valid also for us. For example, to a women's religious community, Hildegard wrote thus: "The spiritual life must be taken care of with much dedication. In the beginning the effort is bitter. Because it calls for the renunciation of fancies, the pleasure of the flesh and other similar things. But if it allows itself to be fascinated by holiness, a holy soul will find sweet and lovable its very contempt for the world. It is only necessary to intelligently pay attention so that the soul does not shrivel" (E. Gronau, Hildegard. Vita di una donna profetica alle origini dell'eta moderna, Milan, 1996, p. 402).

And when the emperor Frederick Barbarossa caused an ecclesial schism by opposing three anti-popes to the legitimate Pope Alexander III, Hildegard, inspired by her visions, did not hesitate to remind him that he also, the emperor, was subject to the judgment of God. With the audacity that characterizes every prophet, she wrote these words to the emperor as God speaking: "Woe, woe to this wicked behavior of evil-doers who scorn me! Listen, O king, if you wish to live! Otherwise my sword will run you through!" (Ibid., p. 412).

With the spiritual authority with which she was gifted, in the last years of her life Hildegard began to travel, despite her advanced age and the difficult conditions of the journeys, to talk of God to the people. All listened to her eagerly, even when she took a severe tone: They considered her a messenger sent by God. Above all she called monastic communities and the clergy to a life in keeping with their vocation. In a particular way, Hildegard opposed the movement of German Cathars. They -- Cathar literally means "pure" -- advocated a radical reform of the Church, above all to combat the abuses of the clergy. She reproved them harshly for wishing to subvert the very nature of the Church, reminding them that a true renewal of the ecclesial community is not achieved so much with a change of structures, but by a sincere spirit of penance and an active path of conversion. This is a message that we must never forget.

Let us always invoke the Holy Spirit, so that he will raise up in the Church holy and courageous women, like St. Hildegard of Bingen, who, valuing the gifts received from God, will make their precious and specific contribution to the spiritual growth of our communities and of the Church in our time.